A team of researchers has developed a bioengineered endometrial model to study processes as important as they are unknown to science: the implantation of an embryo, on which the continuation of pregnancy depends, and the first communication with the mother.

The artificial endometrium favored the development of the embryo after implantation, which made it possible to analyze the earliest embryonic stages (12-14 days after fertilization), which have until now been practically unexplored.

First mother-child communication

The researchers observed that embryos implanted in the artificial endometrium reached several developmental milestones, such as the appearance of specialized cell types and the establishment of others that are precursors to placental development.

The developing embryo implants into the uterine lining (endometrium) a week after fertilization, and this is where one of the least-known stages to science begins, due to the difficulty of observing the embryo during and after implantation.

The team tested their model using early-stage human embryos donated by people who had undergone in vitro fertilization (IVF) and discovered that the embryo went through the expected stages of adhesion and implantation in the artificial endometrium.

Cell-by-cell analysis at the implantation sites allowed them to discover the first 'cellular communication' between the embryo and the endometrium, which is necessary for creating the structures through which a mother and child exchange oxygen and nutrients during pregnancy.

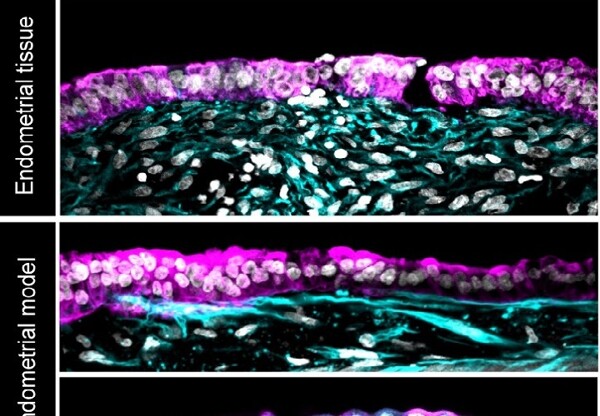

The authors explain that the artificial endometrium achieved the same cellular architecture as the donated tissue and had the same response to hormonal stimulation, indicating that it could be receptive to embryo implantation.

The scientists isolated two types of essential cells from endometrial tissue donated by healthy people who had undergone biopsies to recreate that tissue artificially: epithelial and stromal cells.

'Understanding embryo implantation and its development immediately after is of great clinical relevance, as these stages are particularly prone to failure, especially in IVF processes,' explains one of the authors, Peter Rugg-Gunn, a researcher at the Babraham Institute.

On Tuesday, the journal Cell describes in a scientific article how the first artificial uterine lining was designed, capable of responding to embryo implantation in the same way as a woman's endometrium during pregnancy, producing the essential mechanisms to 'nourish' it.

The engineering behind the artificial endometrium

To achieve this understanding, Rugg-Gunn and his team managed to replicate in three dimensions (3D) the complex physiological properties and cellular composition of the uterine lining.

After implantation, the embryos increased the secretion of certain proteins characteristic of pregnancy and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), which is used in pregnancy tests.

'We were excited to see that our system was releasing the essential factors needed to nourish the embryo during the first weeks of pregnancy,' the statement says.

At the same time, they used information from the donated tissue to identify the key components that give structure to the uterine lining. The researchers were able to incorporate these components, along with the stromal cells, into a special gel to promote the growth of cells into a thick layer. Subsequently, they added epithelial cells that spread over the surface of the stromal cells.

'We are immensely grateful to the people who donate surplus embryos,' concludes another of the authors, Sarah Elderkin, from the Babraham Institute.

Understanding this stage better, Rugg-Gunn emphasizes, is key to finding answers about infertility, miscarriages, and conditions like preeclampsia.

'Now we can better understand the first moments of embryonic development and better understand how that first synchronized communication between mother and baby occurs, which is fundamental for both to stay healthy. Previous models had not been able to achieve this, so this has been a tremendous advance,' Rugg-Gunn said in a statement.

This work is the result of a collaboration between scientists from the Babraham Institute in Cambridge (UK) and Stanford University in the USA.